JavaScript Fundamentals

Introduction to JavaScript

JavaScript was created in 1995 by Brendan Eich while he was working at Netscape. It was originally called Mocha, then renamed to LiveScript, and finally to JavaScript. Today, JavaScript is one of the most popular programming languages in the world, primarily used for web development.

JavaScript consists of three main components:

- ECMAScript: The core language specification

- DOM (Document Object Model): Allows JavaScript to interact with HTML and CSS

- BOM (Browser Object Model): Allows JavaScript to interact with the browser

Variables and Data Types

Variable Basics

In JavaScript, variables are containers for storing data values. Here's how to create and use them:

// Declaring variables

let name = "John"; // Using let (recommended)

var age = 30; // Using var (older style)

const PI = 3.14; // Using const (for values that won't change)

Important rules for variables:

- Cannot start with digits or special characters (except $ and _)

-

Use camelCase by convention (e.g.,

firstName,totalAmount) - JavaScript is dynamically typed (you don't need to specify the type)

- In contrast, languages like Java and C# are statically typed

Data Types

JavaScript has two main categories of data types:

1. Primitive Types

These are simple, immutable data types:

-

undefined: A variable that has been declared but not assigned a value

let undeclaredVar; console.log(typeof undeclaredVar); // undefined -

null: Represents the intentional absence of any object value

let emptyValue = null; console.log(null == undefined); // true (loose equality) console.log(null === undefined); // false (strict equality) -

NaN: Stands for "Not a Number" - a special numeric value indicating an invalid number

console.log('a' / 2); // NaN console.log(NaN == NaN); // false (NaN doesn't equal anything, even itself) -

string: Text data (immutable in JavaScript)

let greeting = "Hello"; // Strings in JavaScript are immutable - operations create new strings let newGreeting = greeting + " World"; // Creates a new string -

boolean: true or false values

let isActive = true; let isComplete = false; -

symbol: A unique and immutable primitive value

let s1 = Symbol(); // Creates a new unique value console.log(Symbol() == Symbol()); // false -

bigint: For representing large integers

let bigNumber = 123456789012345678901234567890n; // The 'n' suffix makes it a BigInt

2. Complex Types

These are more complex data structures:

-

Object: A collection of properties

(key-value pairs)

let person = { name: "John", age: 25, isEmployed: true }; // Accessing properties console.log(person.name); // Using dot notation console.log(person["age"]); // Using array notation // Adding/modifying properties person.location = "New York"; // Deleting properties delete person.age; // Checking if a property exists console.log("name" in person); // true

Helpful Features

Numeric Separator

For better readability of large numbers: It's important to note that all numbers in JavaScript are floating-point numbers.

let amount = 120_201_123.05; // Same as 120201123.05

let billion = 1_000_000_000;

let binary = 0b1010_1010; // Binary

let hex = 0x1A_2B_3C; // Hexadecimal

Boolean Conversion

The Boolean() function converts values to boolean:

// These convert to true

Boolean("Hello"); // Non-empty string

Boolean(42); // Non-zero number

Boolean({}); // Any object

// These convert to false

Boolean(""); // Empty string

Boolean(0); // Zero

Boolean(NaN); // Not a Number

Boolean(null); // Null

Boolean(undefined); // Undefined

String Features

Template Literals

let name = "Sarah";

let greeting = `Hello, I'm ${name}!`; // String interpolation

String Access

let word = "Hello";

console.log(word[0]); // "H" (first character)

console.log(word[word.length - 1]); // "o" (last character)

String Conversion

let num = 42;

let str1 = String(num); // "42"

let str2 = num + ""; // "42"

let str3 = num.toString(); // "42" (doesn't work for undefined and null)

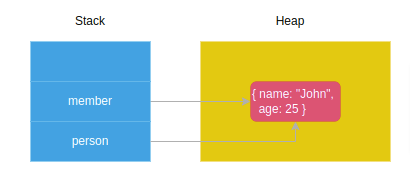

Value Types vs Reference Types

Understanding how JavaScript stores and passes values is crucial:

Primitive vs Reference Values

- Primitive values (like numbers, strings) are stored directly in memory (on the stack)

- Reference values (objects, arrays, functions) store a reference pointing to the actual data (on the heap)

When you assign or pass primitive values, JavaScript creates copies:

let a = 5;

let b = a; // 'b' gets a copy of the value

a = 10; // Changing 'a' doesn't affect 'b'

console.log(b); // Still 5

When you assign or pass objects, JavaScript copies the reference, not the actual data:

let obj1 = {name: "John"};

let obj2 = obj1; // Both variables reference the same object

obj1.name = "Mike"; // Changes affect both variables

console.log(obj2.name); // "Mike"

This diagram helps visualize it:

| Stack (Fixed size) | Heap (Dynamic size) |

|---|---|

| Primitive values | Object data |

| References to objects → | ← Referenced by stack variables |

Arrays

Arrays are special objects used to store ordered collections:

// Creating arrays

let colors = ["red", "green", "blue"];

let numbers = new Array(1, 2, 3); // Using constructor

let emptyWithSize = new Array(5); // Creates array with 5 empty slots

// Common array operations

colors.push("yellow"); // Add to end: ["red", "green", "blue", "yellow"]

colors.unshift("purple"); // Add to beginning: ["purple", "red", "green", "blue", "yellow"]

colors.pop(); // Remove from end: ["purple", "red", "green", "blue"]

colors.shift(); // Remove from beginning: ["red", "green", "blue"]

let position = colors.indexOf("green"); // Find index: 1

let isArray = Array.isArray(colors); // Check if array: true

Operators

Arithmetic Operators

JavaScript handles type conversion automatically in arithmetic operations:

console.log(5 + 2); // 7

console.log("5" + 2); // "52" (string concatenation)

console.log("5" - 2); // 3 (string converted to number)

console.log("5" * 2); // 10 (string converted to number)

Value Conversion

Using the unary plus/minus to convert values:

let str = "10";

console.log(+str); // 10 (number)

console.log(-str); // -10 (number)

console.log(+true); // 1

console.log(+false); // 0

Increment/Decrement Operators

There are important differences between prefix and postfix:

// Prefix (++x) - increments first, then uses the value

let a = 5;

let b = ++a; // a = 6, b = 6

// Postfix (x++) - uses the original value, then increments

let c = 5;

let d = c++; // c = 6, d = 5

Control Flow Statements

JavaScript provides various ways to control program flow:

// if statement

if (condition) {

// code to execute if condition is true

} else if (anotherCondition) {

// code to execute if anotherCondition is true

} else {

// code to execute if no conditions are true

}

// Ternary operator

let result = condition ? valueIfTrue : valueIfFalse;

// Switch statement

switch (expression) {

case value1:

// code when expression equals value1

break;

case value2:

// code when expression equals value2

break;

default:

// code when no cases match

}

// Loops

for (let i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

// repeats 5 times

}

while (condition) {

// executes as long as condition is true

}

do {

// executes at least once, then as long as condition is true

} while (condition);

// break exits the loop, continue skips to next iteration

JavaScript Functions

Basic Function Behavior

Return Values

- Every function in JavaScript implicitly returns undefined unless you explicitly return another value

The Arguments Object

- Inside a function, you can access an object called arguments that contains all arguments passed to the function

- The arguments object behaves like an array though it is not an instance of the Array type

-

arguments.lengthshows the number of actual arguments passed to the function

function add(x, y = 1, z = 2) {

console.log(arguments.length);

return x + y + z;

}

add(10); // outputs: 1

add(10, 20); // outputs: 2

add(10, 20, 30); // outputs: 3

Hoisting

Variable Hoisting

-

Var hoisting: Variables declared with

varare hoisted to the top of their scope and initialized with undefined -

Let hoisting: Variables declared with

letare also hoisted but not initialized (creating a "temporal dead zone")

// With var

console.log(counter); // outputs: undefined

var counter = 1;

// With let

console.log(counter); // ReferenceError: Cannot access 'counter' before initialization

let counter = 1;

Function Hoisting

- Function declarations are hoisted completely (both declaration and definition)

- Function expressions, arrow functions, and class expressions are NOT hoisted

// This works - function declaration is hoisted

sayHello();

function sayHello() {

console.log("Hello!");

}

// This fails - function expression is not hoisted

sayGoodbye(); // TypeError: sayGoodbye is not a function

var sayGoodbye = function() {

console.log("Goodbye!");

};

Parameters and Arguments

Parameter Default Values

- In JavaScript, parameters have a default value of undefined if no argument is provided

- You can set explicit default values for parameters:

function greet(name = "Guest") {

return `Hello, ${name}!`;

}

greet(); // "Hello, Guest!"

greet("John"); // "Hello, John!"

Passing Arguments

Primitives (Pass by Value)

- Primitive values (strings, numbers, booleans) are passed by value

- Changes to parameters inside the function do not affect the original variables

function increment(x) {

x += 1;

console.log("Inside function:", x);

}

let num = 5;

increment(num); // Inside function: 6

console.log(num); // Still 5

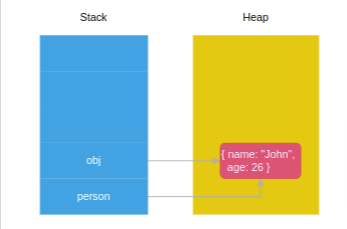

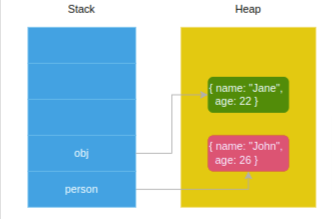

Objects (Pass by Reference-like Behavior)

- Objects are passed by reference-like behavior

- Modifying object properties inside a function affects the original object

- However, reassigning the parameter to a new object does not affect the original reference

let person = {

name: "John",

age: 25

};

function increaseAge(obj) {

obj.age += 1; // Modifies the original object

obj = { name: "Jane", age: 22 }; // Local reassignment, doesn't affect original

}

increaseAge(person);

console.log(person); // { name: "John", age: 26 }

Another example:

const styles = { color: "red" };

function change(styles) {

styles = { background: "black" }; // Local reassignment, no effect on original

}

change(styles);

console.log(styles); // { color: 'red' }

Named Parameters

- JavaScript doesn't support true named parameters like some languages

-

To skip parameters, you must use

undefined:

function createDiv(height, width, border) {

// Function implementation

}

// To only set border, you must use:

createDiv(undefined, undefined, 'solid 5px blue');

Better Alternative: Object Parameters

- The most effective way to handle optional parameters is by using an object parameter:

function createDiv(options = {}) {

const {

height = '100px',

width = '100px',

border = 'none'

} = options;

// Function implementation using height, width, border

}

// Call with only needed parameters

createDiv({ border: 'solid 5px blue' });

First-Class Functions

- In JavaScript, functions are first-class citizens

-

They can be:

- Stored in variables

- Passed as arguments to other functions

- Returned from other functions

- Stored in data structures like arrays and objects

// Function stored in variable

const add = function(a, b) { return a + b; };

// Function passed as argument

[1, 2, 3].map(function(x) { return x * 2; });

// Function returned from another function

function createMultiplier(factor) {

return function(x) {

return x * factor;

};

}

const double = createMultiplier(2);

console.log(double(5)); // 10

JavaScript Objects & Prototypes

Constructor Functions

Constructor functions are a way to create multiple objects with the same structure and behavior.

function Person(firstName, lastName) {

this.firstName = firstName;

this.lastName = lastName;

this.getFullName = function() {

return this.firstName + " " + this.lastName;

};

}

// Create a new Person object

let person = new Person("John", "Doe");

console.log(person.getFullName()); // "John Doe"

Key Points About Constructor Functions:

-

Naming Convention: Constructor functions start with a capital letter (e.g.,

Person) to distinguish them from regular functions. -

The

newKeyword: When calling a constructor withnew:- A new empty object is created

thisis bound to that new object- The function code executes

- The new object is returned automatically

-

Memory Inefficiency Problem: The original approach creates a new copy of methods like

getFullName()for each instance, which wastes memory.

Handling Constructor Calls Without new

If a constructor function is called without the

new keyword, it executes as a regular function, and

this refers to the global object (or

undefined in strict mode):

// Safeguard a constructor function

function Person(firstName, lastName) {

// Check if called without new

if (!new.target) {

return new Person(firstName, lastName);

}

this.firstName = firstName;

this.lastName = lastName;

}

// This still works correctly

let person = Person("John", "Doe");

console.log(person.firstName); // "John"

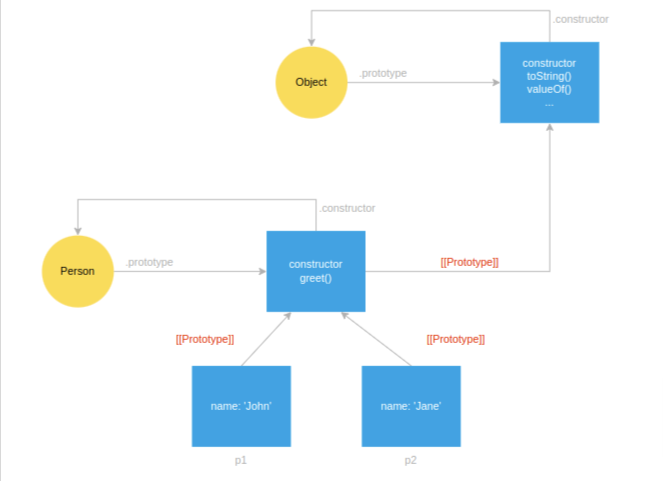

Prototypes

Every JavaScript object has a special property called

prototype, which enables objects to inherit

features from one another.

How Prototypes Work:

-

Every JavaScript function has a property called

prototype(which is itself an object) -

When you use a function as a constructor with

new, the created object gets linked to the constructor'sprototype -

When you try to access a property on an object:

- First, JavaScript looks for the property on the object itself

- If not found, it looks in the object's prototype

- If still not found, it looks in the prototype's prototype, and so on (forming the "prototype chain")

-

The chain ends when a prototype is

null

Using Prototypes for Method Sharing

Instead of defining methods inside the constructor (which creates copies), we can add them to the prototype:

function Person(firstName, lastName) {

this.firstName = firstName;

this.lastName = lastName;

// Notice: no methods defined here

}

// Add method to the prototype (shared by all instances)

Person.prototype.getFullName = function() {

return this.firstName + " " + this.lastName;

};

let person1 = new Person("John", "Doe");

let person2 = new Person("Jane", "Smith");

console.log(person1.getFullName()); // "John Doe"

console.log(person2.getFullName()); // "Jane Smith"

// Both instances share the same method

console.log(person1.getFullName === person2.getFullName); // true

Prototype Chain Relationships

Every constructor function's prototype is linked to

Object.prototype:

// The constructor property points back to the function

console.log(Person.prototype.constructor === Person); // true

// Person's prototype is linked to Object.prototype

console.log(Object.getPrototypeOf(Person.prototype) === Object.prototype); // true

// Ways to access an object's prototype

let p = new Person("John", "Doe");

console.log(Person.prototype === Object.getPrototypeOf(p)); // true

console.log(Person.prototype === p.constructor.prototype); // true

Prototypal Inheritance

In JavaScript, objects can inherit from other objects - this is called prototypal inheritance.

Using __proto__ (Legacy Method)

let person = {

name: "John Doe",

greet: function() {

return "Hi, I'm " + this.name;

}

};

let teacher = {

teach: function(subject) {

return "I can teach " + subject;

}

};

// Make teacher inherit from person

teacher.__proto__ = person;

console.log(teacher.greet()); // "Hi, I'm John Doe"

console.log(teacher.teach("JavaScript")); // "I can teach JavaScript"

Modern Ways to Create Inheritance

ES5 Method:

let person = {

name: "John Doe",

greet: function() {

return "Hi, I'm " + this.name;

}

};

// Create a new object with person as its prototype

let teacher = Object.create(person);

teacher.teach = function(subject) {

return "I can teach " + subject;

};

console.log(Object.getPrototypeOf(teacher) === person); // true

ES6 Method:

class Person {

constructor(name) {

this.name = name;

}

greet() {

return "Hi, I'm " + this.name;

}

}

class Teacher extends Person {

constructor(name) {

super(name);

}

teach(subject) {

return "I can teach " + subject;

}

}

Object Properties

JavaScript objects have two types of properties:

- Data Properties: Store values

- Accessor Properties: Functions that get or set values (getters and setters)

Property Attributes

Every property has attributes that control its behavior:

Data Properties:

- Configurable: If false, the property cannot be deleted or have its attributes changed

- Enumerable: If true, the property appears in for...in loops

- Writable: If false, the property's value cannot be changed

- Value: The actual value of the property

Accessor Properties:

- Configurable: Same as above

- Enumerable: Same as above

- Get: The getter function

- Set: The setter function

Defining Properties

You can define or modify property attributes using

Object.defineProperty() or

Object.defineProperties():

let product = {};

Object.defineProperties(product, {

name: {

value: 'Smartphone',

enumerable: true // Will show up in for...in loops

},

price: {

value: 799,

writable: true // Can be changed

},

tax: {

value: 0.1,

configurable: false // Cannot be deleted

},

netPrice: {

// Accessor property with getter

get: function() {

return this.price * (1 + this.tax);

}

}

});

console.log(product.name); // "Smartphone"

console.log(product.netPrice); // 878.9

Property Enumeration and Ownership

-

for...inloops iterate over all enumerable properties (including inherited ones) -

obj.propertyIsEnumerable()checks if a property is enumerable -

obj.hasOwnProperty()checks if a property belongs to the object itself (not inherited)

Computed Properties (ES6)

Allow you to use expressions as property names:

let propName = 'dynamicProperty';

let obj = {

[propName]: 'value' // Creates property named "dynamicProperty"

};

// Useful for creating objects dynamically

function createObj(key, value) {

return { [key]: value };

}

let user = createObj('username', 'john_doe');

console.log(user); // { username: 'john_doe' }

Classes (ES6)

ES6 introduced a cleaner syntax for creating objects and implementing inheritance:

class Person {

// Class properties

#firstName; // Private property (with # prefix)

#lastName; // Private property

static count = 0; // Static property (shared by all instances)

// Constructor

constructor(firstName, lastName) {

this.#firstName = firstName;

this.#lastName = lastName;

Person.count++; // Increment the counter

}

// Instance method

getFullName() {

return `${this.#firstName} ${this.#lastName}`;

}

// Private method

#validateName(name) {

return typeof name === 'string' && name.trim().length >= 2;

}

// Static method

static createAnonymous() {

return new Person("Anonymous", "User");

}

}

// Create an instance

let person = new Person("John", "Doe");

console.log(person.getFullName()); // "John Doe"

console.log(Person.count); // 1

Inheritance with Classes

class Employee extends Person {

#position;

constructor(firstName, lastName, position) {

super(firstName, lastName); // Call parent constructor

this.#position = position;

}

getRole() {

return this.#position;

}

// Override parent method

getFullName() {

return `${super.getFullName()} (${this.#position})`;

}

}

let employee = new Employee("Jane", "Smith", "Developer");

console.log(employee.getFullName()); // "Jane Smith (Developer)"

JavaScript Advanced Functions

Functions as Objects

In JavaScript, all functions are actually objects - they are

instances of the Function type. This means

functions can:

- Have properties and methods

- Be passed as arguments to other functions

- Be assigned to variables

- Be returned from other functions

Closures

A closure is a function that retains access to its lexical scope (variables from its parent function) even after the parent function has finished executing.

How Closures Work

- When you define a function inside another function, the inner function has access to the variables of the outer function

- If the inner function is returned or otherwise preserved (like stored in a variable or passed as a callback), it maintains access to those variables

- This preserved environment is called a closure

Practical Example of Closure Issues

Consider this classic problem with loops and

setTimeout:

for (var index = 1; index <= 3; index++) {

setTimeout(function () {

console.log('after ' + index + ' second(s): ' + index);

}, index * 1000);

}

// Output:

// after 4 second(s): 4

// after 4 second(s): 4

// after 4 second(s): 4

What happened? By the time the first callback executes (after

1000ms), the loop has already completed, and

index is 4. All three functions in the

closure share the same index variable.

Solutions to the Loop Closure Problem

Solution 1: IIFE (Immediately Invoked Function Expression)

Create a new scope for each iteration using an IIFE:

for (var index = 1; index <= 3; index++) {

(function(currentIndex) {

setTimeout(function () {

console.log('after ' + currentIndex + ' second(s): ' + currentIndex);

}, currentIndex * 1000);

})(index);

}

// Output:

// after 1 second(s): 1

// after 2 second(s): 2

// after 3 second(s): 3

Solution 2: Block Scoping with let (ES6+)

The let keyword creates a new binding for each loop

iteration:

for (let index = 1; index <= 3; index++) {

setTimeout(function () {

console.log('after ' + index + ' second(s): ' + index);

}, index * 1000);

}

// Output:

// after 1 second(s): 1

// after 2 second(s): 2

// after 3 second(s): 3

The this Keyword in Functions

The value of this inside a function depends on how

the function is called, not where it's defined.

Common this Binding Issues

function Car() {

this.speed = 0;

this.speedUp = function(speed) {

this.speed = speed;

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(this.speed); // undefined

}, 1000);

};

}

let car = new Car();

car.speedUp(50);

Inside the setTimeout callback,

this doesn't refer to the Car instance.

Instead, it refers to the global object (or

undefined in strict mode).

Solutions to the this Problem

Solution 1: Preserve this with a variable

function Car() {

this.speed = 0;

this.speedUp = function(speed) {

this.speed = speed;

let self = this; // Store reference to 'this'

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(self.speed); // 50

}, 1000);

};

}

Solution 2: Use an arrow function (ES6+)

function Car() {

this.speed = 0;

this.speedUp = function(speed) {

this.speed = speed;

setTimeout(() => {

console.log(this.speed); // 50

}, 1000);

};

}

Arrow functions inherit this from their surrounding

scope, which solves the problem elegantly.

Arrow Functions

Arrow functions were introduced in ES6 and provide more concise

syntax, plus they handle this differently.

Syntax

// Traditional function

function add(a, b) {

return a + b;

}

// Arrow function

const add = (a, b) => a + b;

Special Characteristics of Arrow Functions

-

No

thisbinding-

Arrow functions don't have their own

this- they inherit it from the parent scope -

This makes them ideal for callbacks inside methods

where you want to access the parent's

this

-

Arrow functions don't have their own

-

No

argumentsobject-

Arrow functions don't have their own

argumentsobject -

They can access the

argumentsof their containing function

function show() { return (x) => x + arguments[0]; } let display = show(10, 20); let result = display(5); console.log(result); // 15 (5 + 10) // Here, arguments[0] refers to the first argument (10) of the show() function -

Arrow functions don't have their own

-

No

new.target- Arrow functions cannot be used as constructors

-

They don't have access to the

new.targetkeyword

-

No

prototypeproperty-

Unlike regular functions, arrow functions don't

have a

prototypeproperty

-

Unlike regular functions, arrow functions don't

have a

When NOT to Use Arrow Functions

Arrow functions are not suitable for:

-

Event handlers where

thisshould refer to the event target -

Object methods where

thisshould refer to the object -

Prototype methods where

thisshould refer to the instance -

Functions that need to use the

argumentsobject -

Functions that need to be used as constructors with

new

Callbacks and Higher-Order Functions

Callbacks

A callback is a function passed as an argument to another function, to be executed later.

function fetchData(callback) {

// Simulate API call

setTimeout(() => {

const data = { name: "John", age: 30 };

callback(data);

}, 1000);

}

fetchData(function(data) {

console.log(data); // { name: "John", age: 30 }

});

Higher-Order Functions

A higher-order function is a function that accepts another function as an argument or returns a function.

// Higher-order function that accepts a function as argument

function calculate(operation, a, b) {

return operation(a, b);

}

// Functions to pass as arguments

const add = (x, y) => x + y;

const multiply = (x, y) => x * y;

console.log(calculate(add, 5, 3)); // 8

console.log(calculate(multiply, 5, 3)); // 15

// Higher-order function that returns a function

function createMultiplier(factor) {

return function(number) {

return number * factor;

};

}

const double = createMultiplier(2);

const triple = createMultiplier(3);

console.log(double(5)); // 10

console.log(triple(5)); // 15

Higher-order functions are a core concept in functional programming and are widely used in JavaScript for operations like array mapping, filtering, and reducing.

Function Binding

Sometimes you need to explicitly set the value of

this in a function, regardless of how it's

called. JavaScript provides three methods for this:

1. bind()

Creates a new function with this permanently bound

to a specific value:

const person = {

name: "John",

greet: function() {

console.log(`Hello, my name is ${this.name}`);

}

};

const greetFunction = person.greet;

greetFunction(); // "Hello, my name is undefined"

const boundGreet = person.greet.bind(person);

boundGreet(); // "Hello, my name is John"

2. call()

Calls a function with a specified this value and

arguments:

function greet(greeting) {

console.log(`${greeting}, my name is ${this.name}`);

}

const person = { name: "John" };

greet.call(person, "Hello"); // "Hello, my name is John"

3. apply()

Similar to call(), but arguments are passed as an

array:

function introduce(greeting, message) {

console.log(`${greeting}, my name is ${this.name}. ${message}`);

}

const person = { name: "John" };

introduce.apply(person, ["Hello", "Nice to meet you"]);

// "Hello, my name is John. Nice to meet you"

JavaScript Promises & Async/Await

Introduction to Asynchronous JavaScript

Complete Example of Asynchronous Javascript

JavaScript uses various patterns to handle asynchronous operations:

- Callbacks (traditional approach)

- Promises (introduced in ES6/ES2015)

- Async/Await (introduced in ES2017)

Each new pattern builds on the previous one, making asynchronous code progressively more readable and maintainable.

Promises

A Promise is an object representing the eventual completion or failure of an asynchronous operation. It serves as a placeholder for a value that may not be available yet.

Creating Promises

function getUsers() {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

// Asynchronous code goes here, such as:

// - API calls

// - Database operations

// - File system operations

// On success:

resolve(users);

// On failure:

// reject(error);

});

}

A Promise can be in one of three states:

- Pending: Initial state, neither fulfilled nor rejected

- Fulfilled: Operation completed successfully

- Rejected: Operation failed

Consuming Promises

You can attach callbacks to promises using .then(),

.catch(), and .finally() methods:

getUsers()

.then((users) => {

// This executes when the promise is fulfilled

console.log(users);

})

.catch((error) => {

// This executes when the promise is rejected

console.log(error);

})

.finally(() => {

// This executes regardless of success or failure

console.log('Operation completed');

});

Alternative Promise Handling Syntax

You can also provide both success and error handlers directly to

.then():

// Option 1: Separate handler functions

function onFulfilled(users) { console.log(users); }

function onRejected(error) { console.log(error); }

getUsers().then(onFulfilled, onRejected);

// Option 2: Inline handlers

getUsers().then(

(users) => console.log(users),

(error) => console.log(error)

);

However, using .catch() is generally preferred for

error handling as it also catches errors thrown in

.then() callbacks.

Creating Pre-Resolved or Pre-Rejected Promises

// Create a pre-resolved promise

Promise.resolve('Success').then(console.log); // Success

// Create a pre-rejected promise

Promise.reject('Error').catch(console.log); // Error

// Using finally

Promise.resolve('Success')

.finally(() => console.log('Done')); // Done

Promise Combinators

JavaScript provides several methods to work with multiple promises simultaneously:

1. Promise.all()

Waits for all promises to resolve, or rejects if any promise rejects:

// All promises resolve

Promise.all([

Promise.resolve(1),

Promise.resolve(2),

Promise.resolve(3)

]).then(console.log); // [1, 2, 3]

// One promise rejects

Promise.all([

Promise.resolve(1),

Promise.reject('Error'),

Promise.resolve(3)

]).catch(console.log); // Error

Use Promise.all() when you need all operations to

succeed and want to wait for all of them to complete.

2. Promise.race()

Returns the result of the first promise to settle (either resolve or reject):

Promise.race([

Promise.resolve(1),

new Promise(resolve => setTimeout(() => resolve(2), 1000))

]).then(console.log); // 1

Promise.race([

new Promise((_, reject) => setTimeout(() => reject('Timeout'), 500)),

fetch('https://api.example.com/data')

]).then(data => console.log(data))

.catch(error => console.log(error)); // May log "Timeout" if fetch takes longer than 500ms

Use Promise.race() for implementing timeouts or

when you only need the fastest result.

3. Promise.any() (ES2021)

Returns the first promise to fulfill (resolve). It only rejects if all promises reject:

Promise.any([

Promise.reject('Error1'),

Promise.resolve('Success1'),

Promise.resolve('Success2')

]).then(console.log); // Success1

// If all promises reject

Promise.any([

Promise.reject('Error1'),

Promise.reject('Error2')

]).then(console.log)

.catch(error => console.log(error.errors)); // ['Error1', 'Error2']

The key difference between Promise.any() and

Promise.race():

-

Promise.any()waits for the first promise to fulfill (resolve) -

Promise.race()waits for the first promise to settle (either resolve or reject)

4. Promise.allSettled() (ES2020)

Waits for all promises to settle (either resolve or reject) and returns an array with the outcome of each promise:

Promise.allSettled([

Promise.resolve('Success'),

Promise.reject('Error'),

Promise.resolve('Another success')

]).then(results => {

console.log(results);

/* Output:

[

{ status: 'fulfilled', value: 'Success' },

{ status: 'rejected', reason: 'Error' },

{ status: 'fulfilled', value: 'Another success' }

]

*/

});

Use Promise.allSettled() when you want to know the

outcome of each promise regardless of whether some succeed or

fail.

Async/Await

Introduced in ES2017, async/await is syntactic sugar built on top of Promises, making asynchronous code look and behave more like synchronous code.

Basic Syntax

async function functionName() {

// Use await keyword inside async functions

const result = await somePromise();

return result;

}

Key points:

-

Functions with the

asynckeyword always return a Promise -

The

awaitkeyword can only be used insideasyncfunctions -

awaitpauses execution until the Promise resolves

Error Handling with Try/Catch

async function showServiceCost() {

try {

// These lines execute sequentially

let user = await getUser(100);

let services = await getServices(user);

let cost = await getServiceCost(services);

console.log(`The service cost is ${cost}`);

} catch (error) {

// Catches any errors from any of the await expressions

console.log(error);

}

}

Benefits of Async/Await Over Promise Chains

Compare these two equivalent implementations:

Promise Chain:

function showServiceCost() {

return getUser(100)

.then(user => getServices(user))

.then(services => getServiceCost(services))

.then(cost => {

console.log(`The service cost is ${cost}`);

})

.catch(error => {

console.log(error);

});

}

Async/Await:

async function showServiceCost() {

try {

let user = await getUser(100);

let services = await getServices(user);

let cost = await getServiceCost(services);

console.log(`The service cost is ${cost}`);

} catch (error) {

console.log(error);

}

}

The async/await version is:

- More readable (resembles synchronous code)

- Easier to debug (clearer stack traces)

- Simpler to reason about (sequential execution)

Parallel Execution with Async/Await

While sequential awaits are easy to read, they may not be efficient if operations can run in parallel:

// Sequential (slower)

const userData = await fetchUserData(userId);

const productData = await fetchProductData(productId);

// Parallel (faster)

const [userData, productData] = await Promise.all([

fetchUserData(userId),

fetchProductData(productId)

]);

Evolution of Asynchronous Patterns

1. Callback Hell (Pre-ES6)

getUserData(userId, function(userData) {

getUserPosts(userData.id, function(posts) {

getPostComments(posts[0].id, function(comments) {

// Deeply nested and hard to follow

console.log(comments);

}, handleError);

}, handleError);

}, handleError);

2. Promises (ES6/ES2015)

getUserData(userId)

.then(userData => getUserPosts(userData.id))

.then(posts => getPostComments(posts[0].id))

.then(comments => {

console.log(comments);

})

.catch(error => {

console.log('Error:', error);

});

3. Async/Await (ES2017)

async function showUserComments(userId) {

try {

const userData = await getUserData(userId);

const posts = await getUserPosts(userData.id);

const comments = await getPostComments(posts[0].id);

console.log(comments);

} catch (error) {

console.log('Error:', error);

}

}

Each evolution has made asynchronous code progressively more readable and maintainable.

JavaScript Iterators and Generators

Iterators and Iterables

JavaScript ES6 introduced a formal way to iterate through data using iterators and iterables.

What is an Iterable?

An iterable is an object that implements the iterable protocol:

-

It must have a method with the key

Symbol.iterator - This method returns an iterator object

Built-in iterables in JavaScript include:

- Arrays

- Strings

- Maps

- Sets

- DOM collections

What is an Iterator?

An iterator is an object that implements the iterator protocol:

- It must have a

next()method -

This

next()method returns an object with two properties:value: The current value-

done: A boolean indicating whether iteration is complete

The for...of Loop

The for...of loop provides a clean way to iterate

over iterables:

// Basic syntax

for (const value of iterable) {

// code to execute for each value

}

Using for...of with Built-in Iterables

Arrays

// Basic iteration

let scores = [80, 90, 70];

for (const score of scores) {

console.log(score);

}

// Output: 80, 90, 70

// Modifying values (requires let instead of const)

let numbers = [1, 2, 3];

for (let number of numbers) {

number = number * 2;

console.log(number);

}

// Output: 2, 4, 6 (original array remains unchanged)

// Getting index and value with entries()

let colors = ['Red', 'Green', 'Blue'];

for (const [index, color] of colors.entries()) {

console.log(`${color} is at index ${index}`);

}

// Output:

// Red is at index 0

// Green is at index 1

// Blue is at index 2

Strings

let message = 'Hello';

for (const char of message) {

console.log(char);

}

// Output: H, e, l, l, o

Maps

let colors = new Map();

colors.set('red', '#ff0000');

colors.set('green', '#00ff00');

colors.set('blue', '#0000ff');

// Iterating over key-value pairs

for (const entry of colors) {

console.log(entry); // [key, value] array

}

// Output:

// ['red', '#ff0000']

// ['green', '#00ff00']

// ['blue', '#0000ff']

// Destructuring for cleaner code

for (const [name, hex] of colors) {

console.log(`${name} has hex value ${hex}`);

}

// Output:

// red has hex value #ff0000

// green has hex value #00ff00

// blue has hex value #0000ff

Sets

let uniqueNumbers = new Set([1, 2, 3]);

for (const num of uniqueNumbers) {

console.log(num);

}

// Output: 1, 2, 3

Object Destructuring in for...of

You can use object destructuring to extract specific properties:

const ratings = [

{ user: 'John', score: 3 },

{ user: 'Jane', score: 4 },

{ user: 'David', score: 5 },

{ user: 'Peter', score: 2 }

];

// Only extract the score property

let sum = 0;

for (const { score } of ratings) {

sum += score;

}

console.log(`Total scores: ${sum}`); // Output: Total scores: 14

// Extract multiple properties

for (const { user, score } of ratings) {

console.log(`${user} rated ${score}`);

}

// Output:

// John rated 3

// Jane rated 4

// David rated 5

// Peter rated 2

for...of vs for...in

It's important to understand the difference between these two loops:

-

for...of: Iterates over the values of an iterable object -

for...in: Iterates over the enumerable properties of an object

const array = ['a', 'b', 'c'];

// for...of iterates over values

for (const value of array) {

console.log(value);

}

// Output: a, b, c

// for...in iterates over property names (indices for arrays)

for (const key in array) {

console.log(key, array[key]);

}

// Output:

// 0 a

// 1 b

// 2 c

// WARNING: for...in on arrays can be problematic

// If you add properties to Array.prototype, they will also be iterated

Array.prototype.customProperty = 'surprise!';

for (const key in array) {

console.log(key, array[key]);

}

// Output:

// 0 a

// 1 b

// 2 c

// customProperty surprise!

Creating Custom Iterables

To make your own objects iterable, implement the

Symbol.iterator method:

const range = {

from: 1,

to: 5,

// Make the object iterable

[Symbol.iterator]() {

return {

current: this.from,

last: this.to,

// Implement the next() method

next() {

if (this.current <= this.last) {

return { value: this.current++, done: false };

} else {

return { done: true };

}

}

};

}

};

for (const num of range) {

console.log(num);

}

// Output: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

Generators

Generators provide a more powerful and convenient way to create iterators. They allow you to pause and resume execution.

Basic Generator Syntax

function* generate() {

yield 1;

yield 2;

yield 3;

}

const generator = generate();

console.log(generator.next()); // { value: 1, done: false }

console.log(generator.next()); // { value: 2, done: false }

console.log(generator.next()); // { value: 3, done: false }

console.log(generator.next()); // { value: undefined, done: true }

Some key points about generators:

-

You define a generator function with

function* -

Inside a generator,

yieldpauses execution and returns a value -

Each call to

next()resumes execution until the nextyield - When a generator is called, it returns a generator object without executing its body

-

Generator objects are iterable, so you can use them with

for...of

Generator Execution Flow

function* generate() {

console.log('Start');

yield 1;

console.log('After first yield');

yield 2;

console.log('After second yield');

yield 3;

console.log('End');

}

const gen = generate();

console.log('Before first next()');

console.log(gen.next());

console.log('Before second next()');

console.log(gen.next());

Output:

Before first next()

Start

{ value: 1, done: false }

Before second next()

After first yield

{ value: 2, done: false }

Using Generators with for...of

Since generators produce iterators, they work seamlessly with

for...of:

function* colors() {

yield 'red';

yield 'green';

yield 'blue';

}

for (const color of colors()) {

console.log(color);

}

// Output: red, green, blue

Practical Use Cases for Generators

1. Generating Infinite Sequences

function* infiniteSequence() {

let i = 0;

while (true) {

yield i++;

}

}

const numbers = infiniteSequence();

console.log(numbers.next().value); // 0

console.log(numbers.next().value); // 1

console.log(numbers.next().value); // 2

// Can continue indefinitely without memory issues

2. Creating Custom Iterables with Generators

// Much simpler than implementing Symbol.iterator directly

function* rangeGenerator(from, to) {

for (let i = from; i <= to; i++) {

yield i;

}

}

for (const num of rangeGenerator(1, 5)) {

console.log(num);

}

// Output: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5

3. Lazy Evaluation

Generators compute values only when needed:

function* lazyMap(array, mappingFunction) {

for (const item of array) {

yield mappingFunction(item);

}

}

// This doesn't compute all values immediately

const lazyDoubles = lazyMap([1, 2, 3, 4], x => {

console.log(`Computing double of ${x}`);

return x * 2;

});

// Values are computed on demand

for (const value of lazyDoubles) {

console.log(`Got value: ${value}`);

if (value > 4) break; // We stop early, so not all values are computed

}

Output:

Computing double of 1

Got value: 2

Computing double of 2

Got value: 4

Computing double of 3

Got value: 6

4. Async Flow Control (Pre-async/await Era)

Generators were used for async flow control before async/await:

function* fetchUserData() {

try {

const user = yield fetchUser(userId);

const posts = yield fetchPosts(user.id);

const comments = yield fetchComments(posts[0].id);

return comments;

} catch (error) {

console.error(error);

}

}

This pattern was popular with libraries like co and redux-saga.

JavaScript Modules Explained

What Are Modules?

A module is a JavaScript file that:

- Executes in strict mode automatically

- Keeps variables and functions contained (not added to the global scope)

- Allows explicit importing and exporting of code

Basic Module Usage

Exporting Code

You can export variables, functions, and classes from a module:

// lib.js

function display(message) {

console.log(message);

}

// Named export

export { display };

Importing Code

You can import variables, functions, and classes into another module:

// index.js

import { display } from './lib.js';

display("Hello world!");

Using Modules in HTML

To use modules in a web browser, add

type="module" to your script tag:

<script type="module" src="index.js"></script>

Renaming Imports and Exports

You can rename exports when exporting:

// Rename during export

export { display as showMessage };

Or rename imports when importing:

// Rename during import

import { display as showMessage } from './lib.js';

Default Exports

A module can have multiple named exports but only one default export:

// greeting.js

export default function sayHello() {

console.log("Hello!");

}

// Also can have named exports

export const VERSION = '1.0';

When importing a default export:

- Don't use curly braces

- You can name it whatever you want

// Import the default export

import sayHello from './greeting.js';

// Import both default and named exports

import sayHello, { VERSION } from './greeting.js';

Combining Declaration and Export

You can combine variable/function/class declaration with export:

// Direct exports

export const MIN = 1;

export const MAX = 100;

export function count() { /* ... */ }

// Or export multiple items at once

const MIN = 1;

const MAX = 100;

function count() { /* ... */ }

export { MIN, MAX, count };

Namespace Imports

Import all exports from a module as a single object:

import * as utilities from './utilities.js';

// Access exports as properties

utilities.MIN;

utilities.count();

// Access default export (if any)

utilities.default();

Note: You cannot access default exports by name through namespace imports!

Dynamic Imports

The import() function lets you import modules on

demand:

document.querySelector('.btn').addEventListener('click', () => {

// Dynamic import returns a Promise

import('./greeting.js')

.then((greeting) => {

greeting.sayHi();

})

.catch((error) => {

console.error(error);

});

});

With async/await:

document.querySelector('.btn').addEventListener('click', async () => {

try {

const greeting = await import('./greeting.js');

greeting.sayHi();

} catch (error) {

console.error(error);

}

});

Load multiple modules:

Promise.all([

import('./module1.js'),

import('./module2.js')

]).then(([module1, module2]) => {

// Use modules

});

Top-Level Await

Modern JavaScript allows using await directly in

modules (not just in async functions):

// user.mjs

const url = 'https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/users';

const response = await fetch(url);

export const users = await response.json();

// app.mjs

import { users } from './user.mjs';

function render(users) {

return users.map(user => `<div>${user.name}</div>`).join('');

}

try {

document.querySelector('.container').innerHTML = render(users);

} catch (error) {

document.querySelector('.container').innerHTML = error.message;

}

<!-- index.html -->

<div class="container"></div>

<script type="module" src="app.mjs"></script>

When a module uses top-level await:

- It acts like an async function

- Modules that import it will wait for it to complete before executing

JavaScript Symbols Explained

Introduction to Symbols

Symbol is a primitive data type introduced in ES6 (ECMAScript 2015) that represents a unique, immutable value.

Key characteristics:

- Symbols are always unique, even when created with the same description

- They provide a way to create non-colliding object properties

- They are primitive values (not objects)

Creating Symbols

The basic way to create a symbol is using the

Symbol() function:

// Create a symbol with a description (for debugging purposes)

let firstName = Symbol('first name');

let lastName = Symbol('last name');

// Symbols with the same description are still different symbols

let firstName2 = Symbol('first name');

console.log(firstName === firstName2); // false

// Check the type

console.log(typeof firstName); // "symbol"

// Symbols are primitives, not objects

// This will cause an error:

let s = new Symbol(); // TypeError: Symbol is not a constructor

The description parameter is optional and is primarily used for debugging purposes. It has no effect on the symbol's identity.

Using Symbols as Object Properties

One of the main uses of symbols is as unique property keys:

const user = {};

// Using symbols as property keys

const id = Symbol('id');

user[id] = 12345;

// Regular property

user.name = "John";

console.log(user); // {name: "John", Symbol(id): 12345}

console.log(user[id]); // 12345

// Symbols don't show up in regular property enumeration

console.log(Object.keys(user)); // ["name"]

console.log(Object.getOwnPropertyNames(user)); // ["name"]

// To get symbol properties, use:

console.log(Object.getOwnPropertySymbols(user)); // [Symbol(id)]

Global Symbol Registry

JavaScript provides a global symbol registry that allows you to share symbols across your application:

// Create or retrieve a symbol from the global registry

let ssn = Symbol.for('ssn');

// Retrieve the same symbol again

let citizenID = Symbol.for('ssn');

// These reference the same symbol

console.log(ssn === citizenID); // true

// Get the key used to register a symbol

console.log(Symbol.keyFor(citizenID)); // "ssn"

// Regular symbols (not in registry) return undefined

let regularSymbol = Symbol('regular');

console.log(Symbol.keyFor(regularSymbol)); // undefined

The registry ensures that symbols with the same key reference the same underlying symbol value.

Well-Known Symbols

JavaScript defines several built-in symbols called "well-known symbols" that allow you to customize object behavior:

Symbol.hasInstance

Customizes the behavior of the instanceof operator:

class MyArray {

static [Symbol.hasInstance](instance) {

return Array.isArray(instance);

}

}

console.log([] instanceof MyArray); // true

Symbol.iterator

Defines how an object should be iterated, enabling the

for...of loop:

const collection = {

items: ['A', 'B', 'C'],

[Symbol.iterator]() {

let index = 0;

const items = this.items;

return {

next() {

return {

done: index >= items.length,

value: items[index++]

};

}

};

}

};

for (const item of collection) {

console.log(item); // "A", "B", "C"

}

Symbol.isConcatSpreadable

Controls how an object behaves when used with

Array.prototype.concat():

const numbers = [1, 2, 3];

const fakeArray = {

[Symbol.isConcatSpreadable]: true,

length: 2,

0: 4,

1: 5

};

console.log([0].concat(numbers)); // [0, 1, 2, 3]

console.log([0].concat(fakeArray)); // [0, 4, 5]

Symbol.toPrimitive

Customizes how an object is converted to a primitive value:

const user = {

name: "John",

age: 30,

[Symbol.toPrimitive](hint) {

switch (hint) {

case 'number':

return this.age;

case 'string':

return this.name;

default: // 'default' hint

return `${this.name}, ${this.age} years old`;

}

}

};

console.log(+user); // 30 (number conversion)

console.log(String(user)); // "John" (string conversion)

console.log(user + ''); // "John, 30 years old" (default conversion)

Benefits of Using Symbols

- Avoiding property name collisions - especially useful in libraries and frameworks

- Creating "hidden" properties - symbols don't appear in typical property enumeration

- Metaprogramming - customizing JavaScript's built-in behavior

- Implementing protocols - like iteration, through well-known symbols

Limitations

-

Symbols are not completely private - they can be accessed

via

Object.getOwnPropertySymbols() -

They aren't automatically serialized to JSON (

JSON.stringify()ignores symbol properties)

JavaScript Map and Set Collections

Map Object

A Map is a collection of key-value pairs where keys

can be any value (including objects, functions, or primitive

values). Unlike regular objects, Maps maintain the insertion

order of elements and offer better performance for frequent

additions and removals.

Creating a Map

// Create an empty Map

let userRoles = new Map();

// Sample objects to use as keys

let john = {name: 'John Doe'},

lily = {name: 'Lily Bush'},

peter = {name: 'Peter Drucker'};

// Method 1: Add entries using set() method (chainable)

userRoles

.set(john, 'admin')

.set(lily, 'editor')

.set(peter, 'subscriber');

// Method 2: Initialize with nested arrays

let userRoles2 = new Map([

[john, 'admin'],

[lily, 'editor'],

[peter, 'subscriber']

]);

Basic Map Operations

// Get a value by key

userRoles.get(john); // 'admin'

userRoles.get({name: 'Unknown'}); // undefined (not found)

// Check if a key exists

userRoles.has(lily); // true

userRoles.has({name: 'Unknown'}); // false

// Get the number of entries

console.log(userRoles.size); // 3

// Delete an entry

userRoles.delete(john); // true (returns true if element existed and was removed)

// Remove all entries

userRoles.clear();

Iterating Over Maps

Maps provide several methods for iteration:

// Iterate over keys

for (const user of userRoles.keys()) {

console.log(user.name);

}

// Iterate over values

for (let role of userRoles.values()) {

console.log(role);

}

// Iterate over [key, value] pairs (entries)

for (const entry of userRoles.entries()) {

console.log(entry[0].name, entry[1]);

}

// With destructuring (cleaner approach for entries)

for (let [user, role] of userRoles.entries()) {

console.log(`${user.name}: ${role}`);

}

// forEach method (callback receives value, key, map)

userRoles.forEach((role, user) => {

console.log(`${user.name}: ${role}`);

});

Converting Map to Arrays

// Convert keys to an array

const keyArray = [...userRoles.keys()];

// Convert values to an array

const valueArray = [...userRoles.values()];

// Convert entries to array of arrays

const entriesArray = [...userRoles.entries()];

// or simply:

const entriesArray2 = [...userRoles];

WeakMap

A WeakMap is similar to a Map but with some

important differences:

- Keys must be objects (primitive values not allowed)

- Keys are held "weakly" (can be garbage-collected if no other references exist)

- Not enumerable (no iteration methods)

- No

sizeproperty

// Create a WeakMap

const weakMap = new WeakMap();

// Valid - using objects as keys

let obj1 = {};

weakMap.set(obj1, 'value for obj1');

// Available methods

weakMap.get(obj1); // 'value for obj1'

weakMap.has(obj1); // true

weakMap.delete(obj1); // true

Use Cases for WeakMap

- Storing private data for objects

- Associating metadata with objects without preventing garbage collection

- Implementing caches that shouldn't prevent memory cleanup

// Example: Private data

const privateData = new WeakMap();

class User {

constructor(name, age) {

privateData.set(this, { name, age });

}

getName() {

return privateData.get(this).name;

}

getAge() {

return privateData.get(this).age;

}

}

Set Object

A Set is a collection of unique values of any type.

It eliminates duplicate values automatically.

Creating a Set

// Create a Set with initial values (duplicates are automatically removed)

let chars = new Set(['a', 'a', 'b', 'c', 'c']);

console.log(chars); // Set { 'a', 'b', 'c' }

// Create an empty Set and add values

let roles = new Set();

roles.add('admin')

.add('editor')

.add('subscriber');

Basic Set Operations

// Get the number of elements

console.log(chars.size); // 3

// Add elements (chainable)

chars.add('d');

chars.add('e').add('f');

// Check if a value exists

chars.has('a'); // true

chars.has('z'); // false

// Delete an element

chars.delete('f'); // true

// Remove all elements

chars.clear(); // Set{}

Iterating Over Sets

// Basic iteration

for (let role of roles) {

console.log(role);

}

// Using values() method (same as basic iteration)

for (let role of roles.values()) {

console.log(role);

}

// Using keys() method (identical to values() in Sets)

for (let role of roles.keys()) {

console.log(role);

}

// Using entries() method (returns [value, value] pairs)

for (let [key, value] of roles.entries()) {

console.log(key, value); // key and value are identical in Sets

console.log(key === value); // true

}

// forEach method

roles.forEach(role => {

console.log(role.toUpperCase());

});

Converting Sets to Arrays

// Convert Set to Array

const rolesArray = [...roles];

// or

const rolesArray2 = Array.from(roles);

// Useful for creating arrays with unique values

const numbers = [1, 2, 3, 3, 4, 4, 5];

const uniqueNumbers = [...new Set(numbers)]; // [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

WeakSet

A WeakSet is similar to a Set but with important

differences:

- Can only contain objects (no primitive values)

- References to objects are weak (allows garbage collection)

- Not enumerable (no iteration methods)

- No

sizeproperty

// Create a WeakSet

const visitedObjects = new WeakSet();

// Add objects

let obj1 = {id: 1};

let obj2 = {id: 2};

visitedObjects.add(obj1);

visitedObjects.add(obj2);

// Available methods

visitedObjects.has(obj1); // true

visitedObjects.delete(obj1); // true

Use Cases for WeakSet

- Tracking object references without preventing garbage collection

- Marking objects that have been "visited" or "processed"

- Implementing object-capability security patterns

// Example: Tracking processed items

const processedItems = new WeakSet();

function processItem(item) {

if (processedItems.has(item)) {

console.log('Already processed this item');

return;

}

// Process the item...

console.log('Processing:', item);

// Mark as processed

processedItems.add(item);

}

Map vs Object and Set vs Array

Map vs Object

- Maps can use any value as keys (objects, functions, etc.)

- Maps maintain insertion order

- Maps are directly iterable

- Maps have a

sizeproperty - Better performance for frequent additions/removals

Set vs Array

- Sets automatically ensure unique values

-

Sets have efficient value lookup with

has() - Sets don't have index-based access

-

Sets don't have order-specific methods like

sort()

JavaScript Variables and Advanced Operators

Variable Declarations: var, let, and const

JavaScript provides three ways to declare variables:

var, let, and const.

Understanding their differences is crucial for writing effective

JavaScript code.

var

var has function scope and was the original way to

declare variables in JavaScript.

Characteristics:

- Scope: Function-scoped (or global if declared outside a function)

-

Hoisting: Fully hoisted with initialization

to

undefined - Redeclaration: Allows redeclaration of the same variable

- Global Object: When declared globally, creates a property on the global object

// Function scope

function test() {

var x = 10;

if (true) {

var x = 20; // Same variable!

console.log(x); // 20

}

console.log(x); // 20 (not 10)

}

// Hoisting

console.log(y); // undefined (not ReferenceError)

var y = 5;

// Creates global property

var globalVar = "I'm global";

console.log(window.globalVar); // "I'm global" (in browser)

let

let was introduced in ES6 (ES2015) and provides

block scoping.

Characteristics:

- Scope: Block-scoped

{} - Hoisting: Hoisted but not initialized (temporal dead zone)

- Redeclaration: Does not allow redeclaration in the same scope

- Global Object: Does not create a property on the global object

// Block scope

function test() {

let x = 10;

if (true) {

let x = 20; // Different variable

console.log(x); // 20

}

console.log(x); // 10

}

// Temporal dead zone

// console.log(y); // ReferenceError: Cannot access 'y' before initialization

let y = 5;

// No global property

let globalLet = "I'm global";

console.log(window.globalLet); // undefined (in browser)

const

const also has block scope but creates read-only

references.

Characteristics:

- Scope: Block-scoped

{} - Hoisting: Hoisted but not initialized (temporal dead zone)

- Reassignment: Cannot be reassigned

- Mutability: The value itself can be mutable (objects, arrays)

// Basic usage

const PI = 3.14159;

// PI = 3; // TypeError: Assignment to constant variable

// Objects are mutable

const person = { name: "John", age: 30 };

person.age = 31; // OK

console.log(person); // { name: "John", age: 31 }

// person = { name: "Jane" }; // TypeError: Assignment to constant variable

Making Objects Immutable with const

While const prevents reassignment, it doesn't

make objects immutable by default:

// Making objects immutable with Object.freeze()

const immutablePerson = Object.freeze({ name: "John", age: 30 });

// immutablePerson.age = 31; // No error in non-strict mode, but change is not applied

console.log(immutablePerson.age); // 30

// Object.freeze() is shallow

const company = Object.freeze({

name: 'ABC Corp',

address: {

street: 'North 1st Street',

city: 'San Jose',

state: 'CA',

zipcode: 95134

}

});

company.address.country = 'USA'; // Works! (nested object isn't frozen)

console.log(company.address.country); // "USA"

// For deep freezing, you would need a recursive approach

function deepFreeze(obj) {

Object.keys(obj).forEach(prop => {

if (typeof obj[prop] === 'object' && obj[prop] !== null) {

deepFreeze(obj[prop]);

}

});

return Object.freeze(obj);

}

const deepFrozenCompany = deepFreeze({

name: 'XYZ Corp',

address: { city: 'Boston' }

});

// deepFrozenCompany.address.state = 'MA'; // No effect

Arrays with const

Arrays declared with const behave similarly to

objects:

const colors = ['red'];

colors.push('green'); // OK

colors.pop(); // OK

console.log(colors); // ["red"]

// colors = ['blue']; // TypeError: Assignment to constant variable

// To make an array immutable:

const immutableColors = Object.freeze(['red', 'blue']);

// immutableColors.push('green'); // TypeError in strict mode

Using const in Loops

const scores = [75, 80, 95];

// This works - new binding for 'score' in each iteration

for (const score of scores) {

console.log(score); // 75, 80, 95

}

// This works too - block scope creates new 'i' for each loop

for (let i = 0; i < scores.length; i++) {

const currentScore = scores[i];

console.log(currentScore);

}

// This fails - trying to reassign 'i'

// for (const i = 0; i < scores.length; i++) { // TypeError

// console.log(scores[i]);

// }

Variable Declaration Best Practices

-

Default to

const: Useconstfor all variables that don't need to be reassigned -

Use

let: When you need to reassign a variable -

Avoid

var: Unless you specifically need its function-scoping behavior - Declare before use: Always declare variables before using them

Advanced Operators

JavaScript provides several advanced operators that can make your code more concise and expressive.

Logical Assignment Operators

These operators combine logical operations with assignment.

Logical OR Assignment (||=)

Assigns the right operand only if the left operand is falsy.

// x ||= y is equivalent to x = x || y

let title;

title ||= "Untitled"; // title is now "Untitled"

let name = "John";

name ||= "Anonymous"; // name remains "John"

// Beware with falsy values like 0 and ""

let count = 0;

count ||= 5; // count becomes 5 (not always what you want!)

Logical AND Assignment (&&=)

Assigns the right operand only if the left operand is truthy.

// x &&= y is equivalent to x = x && y

let user = { name: "John" };

user &&= user.admin; // user is now undefined (user.admin doesn't exist)

let admin = { name: "Admin", isAdmin: true };

admin &&= admin.isAdmin; // admin is now true

Nullish Coalescing Assignment (??=)

Assigns the right operand only if the left operand is

null or undefined.

// x ??= y is equivalent to x = x ?? y

let username;

username ??= "Guest"; // username is now "Guest"

let displayName = "User123";

displayName ??= "Unknown"; // displayName remains "User123"

// Works properly with other falsy values

let count = 0;

count ??= 5; // count remains 0

Nullish Coalescing Operator (??)

Returns the right operand when the left one is

null or undefined, otherwise returns

the left operand.

// Comparison with logical OR operator

let count = 0;

let result1 = count || 1; // 1 (because 0 is falsy)

let result2 = count ?? 1; // 0 (because 0 is not null/undefined)

let name = "";

let displayName1 = name || "Anonymous"; // "Anonymous" (because "" is falsy)

let displayName2 = name ?? "Anonymous"; // "" (because "" is not null/undefined)

let user;

let defaultUser = user ?? { name: "Guest" }; // defaultUser is { name: "Guest" }

Exponentiation Operator (**)

Raises the left operand to the power of the right operand.

// x ** y is equivalent to Math.pow(x, y)

console.log(2 ** 3); // 8

console.log(10 ** -2); // 0.01

// Can be combined with assignment

let value = 2;

value **= 3; // value is now 8

Short-Circuit Evaluation

Short-circuit evaluation is when the second operand is not evaluated if the first operand determines the result.

// OR (||) short-circuits if the first operand is truthy

console.log(true || someUndefinedFunction()); // true (function never called)

// AND (&&) short-circuits if the first operand is falsy

console.log(false && someUndefinedFunction()); // false (function never called)

// Nullish coalescing (??) short-circuits if the first operand is not null/undefined

console.log("value" ?? someUndefinedFunction()); // "value" (function never called)

Understanding the Temporal Dead Zone

The "temporal dead zone" (TDZ) is the time between

entering a scope where a variable is declared with

let or const and the actual

declaration.

{

// Start of TDZ for x

// console.log(x); // ReferenceError: Cannot access 'x' before initialization

const x = 10; // End of TDZ for x

console.log(x); // 10 (works fine)

}

The TDZ helps catch errors by preventing access to variables before they're properly initialized.

Comparison: var vs let vs const

| Feature | var | let | const |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scope | Function | Block | Block |

| Hoisting | Hoisted with undefined |

Hoisted but not initialized | Hoisted but not initialized |

| Redeclaration | Allowed | Not allowed | Not allowed |

| Reassignment | Allowed | Allowed | Not allowed |

| Added to global object | Yes | No | No |

| Temporal dead zone | No | Yes | Yes |